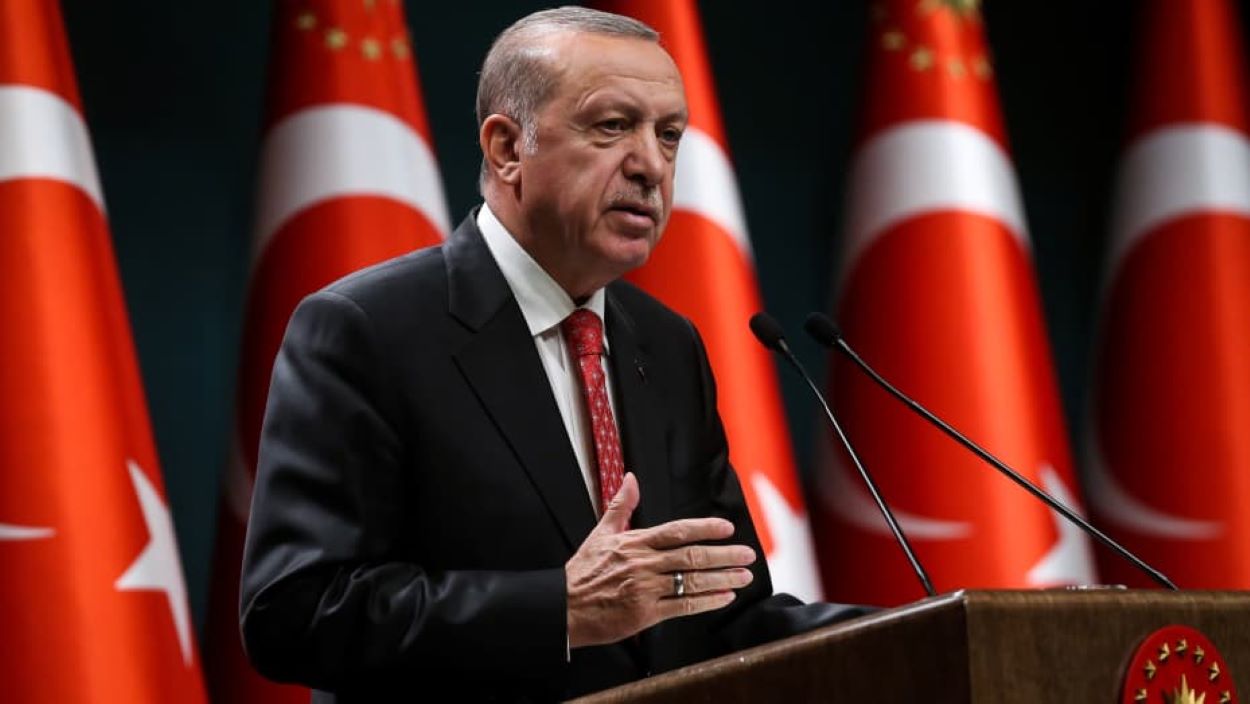

Turkey will never hand over a prized ancient artefact to Israel. President Recep Tayyip Erdogan made this clear on Friday. He spoke about the Siloam inscription, a 2,700-year-old Hebrew tablet. It sits in Istanbul’s archaeology museum today.

The issue reignited diplomatic friction. It started when Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu shared a 1998 story. He said Turkey rebuffed his bid to get the tablet. Back then, Erdogan was Istanbul’s mayor.

Erdogan fired back. He called Netanyahu’s words “spewing hatred.” He added, “Jerusalem is the honour, dignity and glory of all humanity and all Muslims… yet he shamelessly continues to pursue the inscription: we won’t give you that inscription, let alone a single pebble from Jerusalem.”

This spat highlights deep ties to Jerusalem’s past. The city holds holy sites for Jews, Muslims, and Christians. It’s often a flashpoint in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

History of the Siloam Inscription Discovery

The Siloam inscription, also called the Silwan tablet, dates to around 700 BCE. It describes how workers built the Siloam tunnel. This ancient aqueduct runs under Jerusalem. It brought water into the city during King Hezekiah’s time.

French archaeologist Charles Simon Clermont-Ganneau found it in 1880. At that time, Jerusalem was under Ottoman rule. The limestone piece was smuggled out and sent to Constantinople, now Istanbul. It has stayed in Turkey since.

Erdogan to Netanyahu:

[Netanyahu] came out spewing hatred at us because we did not give them the Siloam Inscription.

We won’t give you the inscription, nor even a single pebble belonging to Al-Quds. We will not withdraw our hand from Jerusalem.

pic.twitter.com/5HRW5PR9he

— Ragıp Soylu (@ragipsoylu) September 19, 2025For Israel, the tablet proves early Jewish links to Jerusalem. Netanyahu called it one of Israel’s top finds, after the Dead Sea Scrolls. He shared this at a new road excavation in Silwan, a Palestinian area in east Jerusalem.

Netanyahu’s 1998 Bid and Turkish Refusal

Netanyahu recalled his talk with then-Turkish PM Mesut Yilmaz in 1998. He offered Ottoman artefacts from Israeli museums in trade. “I said: we have thousands of Ottoman artefacts… Let’s do an exchange.” Yilmaz refused.

Netanyahu said Yilmaz feared backlash from Erdogan’s growing Islamist base. Handing over a tablet showing Jerusalem as a Jewish city 2,700 years ago would “outrage” them.

Netanyahu wrapped up: “Well, we’re here. This is our city. Mr Erdogan, it’s not your city, it’s our city. It will always be.” He nodded to Erdogan’s 2020 speech, where he called Jerusalem “our city” due to Ottoman history.

Relations between the two nations have soured further over the Gaza war. Erdogan hit back on Wednesday. He dismissed Netanyahu’s “tantrums” and vowed: “We as Muslims will not step back from our rights over East Jerusalem.”

Jerusalem’s Old City draws pilgrims from all faiths. The Western Wall for Jews, Al-Aqsa Mosque for Muslims, and Church of the Holy Sepulchre for Christians sit close together. This mix often sparks clashes. The Siloam dispute echoes larger issues. It mixes history, politics, and faith. Turkey sees the artefact as Ottoman heritage. Israel views it as proof of ancient roots.