An absolutely staggering 81pc of all government schools in Pakistan are primary schools, which implies that after the primary level, most children have limited opportunities to continue their studies.

This statistic was revealed in the District Education Rankings 2016, jointly launched by education campaigners Alif Ailaan and the Sustainable Development Policy Institute (SDPI) day.

This is a worrying statistic, and according to researchers who worked on the report, one that has been historically observed. Observers say that, as with most other problems in the country, political interests seem to be root cause of this issue as well.

“Politicians have stacked the public sector with low quality primary school teachers for decades – once hired, these primary school teachers needed schools. It is much harder to find and employ higher skill set teachers for middle and high schools,” said Mosharraf Zaidi, who heads the Alif Ailaan campaign.

In the past, MNAs and MPAs have an easier time getting approval for primary schools than secondary or higher schools. “All you need is a two-room building, a teacher who doubles as the headmaster and a peon or two and you’re set,” a district education official said.

This effectively means that there are not enough secondary schools to cater to the large number of students who complete their primary education, leading to dropouts.

A.H. Nayyer, a leading educationist, puts the onus for ensuring student retention squarely on the state’s shoulders.

“According to Article 25A of the Constitution (which deals with the right to education), the state is bound to provide education to all children aged between five and 16. A child who completes primary education is much younger than 16, so the state’s responsibility does not end at the primary level.”

Speaking at the report’s launch, PTI MNA Arif Alvi said that it was absolutely necessary for politicians to take ownership of schools and children in their respective constituencies at an individual level.

ANP leader Mian Ifttikhar Hussain called for a population census, which was key to getting a reliable baseline for ranking districts and tracking the Sustainable Development Goal-targets.

UNDP Country Director Marc-Andre Franche said: “The rankings highlight the systematic inequalities among the districts and the regions in Pakistan. The state of education in the districts of South Punjab, Balochistan and Fata is worse than some of the sub-Saharan African countries, while the districts of North Punjab emulate developed countries like Country-above-USA”.

The report points out that the country’s overall education score had declined by four points after consecutive years of modest improvement, mainly because of an eight-point drop in the retention score. Retention means the number of children enrolled in class 1 who stayed in school at least until class 5.

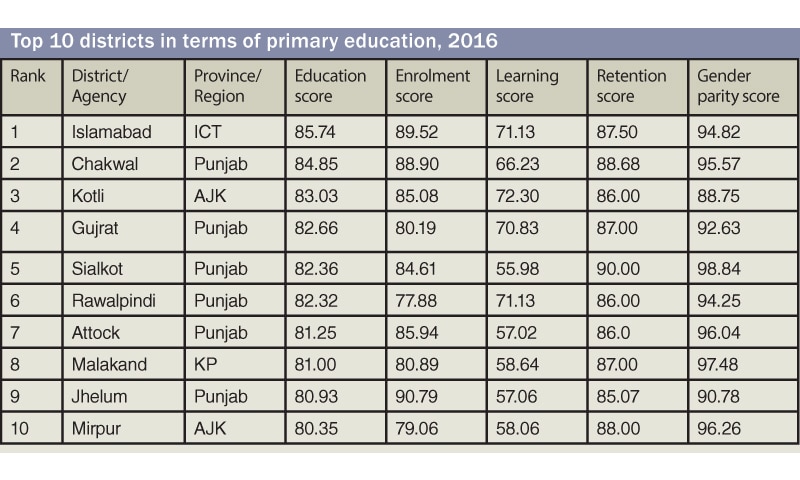

Islamabad tops the list, with the highest retention score of 87, followed by AJK where all 10 districts have scored over 80. Balochistan is at the bottom, where 20 districts have a retention score of below 40pc. Incidentally, Pakistan has the most out-of-school children in the world, around 24 million, and is second only to Nigeria in this dubious honour.

A new index for school completeness also shows that only 52pc of all government schools in the country had complete facilities, namely: toilets, boundary walls, electricity and water.

The federal capital topped both the provincial/regional rankings, as well as the district rankings for primary schools for the first time, with increased learning and enrolment scores.

Rawalpindi, which topped the rankings for primary schools last year, slid five spots to sixth place this year.

Likewise, although Punjab’s education score decreased due to a decline in retention scores, it scored highest in gender parity and school infrastructure. Last year the education score of the province suffered a drop in learning outcomes. However the provincial government responded to this by re-focusing on the quality of education. Consequently, this year Punjab demonstrated a slight improvement in learning outcomes.

While KP demonstrated improvements in both enrolment and gender parity scores, the retention rate of the province also declined. However, nearly half of its schools still lacked basic facilities.

Sindh has the lowest learning outcomes this year with Karachi being the only district in the top 50. The state of school infrastructure there also continued to suffer, as only 23pc of schools could be considered complete.

Though Fata demonstrated an improvement of three per cent in its education score, allowing it to outrank Balochistan, this year’s survey did not contain scores for both north and south Waziristan. FR Kohat, which was unranked in previous years due to non-availability of data, has managed to climb to 39th place.

However, the prime minister’s hometown of Lahore, which is also the second largest city in the country, slipped from third place in last year’s rankings to 22nd place this year. According to the team that complied the report, this was due to lower retention and enrolment rates, as compared to other districts. “For some reason, retention rates are relatively higher in non-urban centres,” a researcher said.